KPMG: Value chains will be disrupted in the future mobility ecosystem

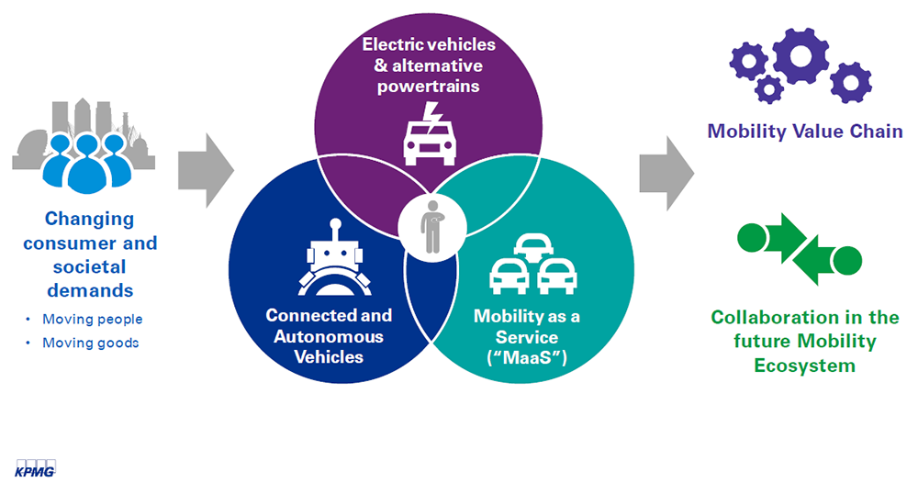

The automotive, transport and wider mobility market is currently at the start of one of the most transformational social, technological and economic shifts of this century, as the way people and products are moved fundamentally changes. This is being driven by the evolution of consumer demand, whilst three converging supply-side trends of vehicle electrification, automation and Mobility as a Service are also responsible. The future of mobility is one of the most pervasive global mega-trends and will have far reaching implications. A plethora of sectors, beyond automotive and transport, will be disrupted. New markets will emerge, whilst some existing markets will decline and maybe vanish altogether. New entrants and start-ups will challenge incumbents, who in turn will look to leverage experience and resources to defend and gain share.

KPMG's Mukarram Bhaiji and Edwin Kemp share their thoughts with TaaS Technology Magazine.

Three key megatrends: electric vehicles (EV) and alternative powertrains, connected and autonomous vehicles (CAV) and Mobility as a Service (MaaS) will disrupt how people and goods will move in the future. These technological advances will replace our current personal vehicle-centric system with a radically more efficient, cleaner, service-based, data enabled and driverless ecosystem, with the consumer sat at its heart. It will seamlessly interact with other transport modes and wider infrastructure. Our view is that this will not be architected by any one company or sector and it will require unprecedented levels of collaboration within the complex ecosystem to develop the right solutions for the future of passenger and goods mobility.

Mobility is critical for population hubs and economies to function and grow. From a consumer perspective, passengers want to get from A to B in an economical, convenient and safe manner. Concerns such as environmental and health impacts are also becoming increasingly important and subject to public policy scrutiny. In contrast, mobility systems today suffer from congestion, inefficiency, human-driven accidents and high prices, which leads to detrimental social and economic consequences.

We are now witnessing a real shift in consumer demands and the way they view mobility. For example, from an economic point of view consumers are transitioning from asset ownership to access, especially in urban areas. KPMG's Global Automotive Executive Survey (2017) found that more than one in three consumers agreed that 50% of today's car owners will no longer want to own their own car by 2025. Similarly, recent Department for Transport statistics show that the percentage of men in England aged 17-20 holding a full UK driver's license has fallen from 51% in the mid-1990s to just 33% in 2016 (and from 81% to 68% for men aged 21-29). This can be partly attributed to the demand for convenience and the resultant emergence of on-demand private car hire firms such as Uber and Lyft, where at the click of a button a car will turn up in minutes. Then from a safety perspective, the emergence of AVs should enable new waves of untapped mobility demand from young people and seniors, offering safe independence where options were previously few.

Commercial goods carriers place similar demands on mobility systems "“ to be economical, safe, efficient and "˜green'. We are already starting to see this play out in HGV platooning trials, most notably in Europe and the US, where this technology is expected to cut operating costs substantially and reduce CO2 emissions by up to 10% (according to the European Automobile Manufacturers Association). Meanwhile, digitally enabled connectivity has led to the emergence of digital freight brokerage companies that seek to address the inefficiency issue evident in the significant proportion of trucks that run empty in Europe and other continents.

The impact of all this will be dramatic. KPMG estimates that in the UK for example, total passenger miles travelled could increase by up to 10% between 2015 and 2030. This will largely arise from additional trips taken by the young and elderly in AVs, as well as greater access to on-demand mobility services providers. These vehicles will increasingly be owned by fleets and will be heavily utilised assets much in the same way taxis currently are, in contrast to the average passenger car which today stands idle 95% of the time. As a result, this could mean a decline in overall car sales by 2030.

That said, our view is that future mobility solutions, and especially AV and MaaS, will have a significant, positive impact on global economies. This will mainly arise from consumer time freed up (not having to drive), more efficient journeys contributing to greater labour productivity and flexibility, as well as the value from greater telco and "˜smart' infrastructure demand and new digital and service sector revenue streams. Indeed, our 2015 analysis for the UK alone estimated the impact to be £51bn added to annual UK GDP by 2030 (or a c. 2.5% increase on current levels). Given the pace of change in the market, that figure is likely to be even higher now.

The growth in consumer spending power from time freed up and new possibilities whilst travelling, as well as the emergence of new vehicle technologies and the maturation of the supporting digital and physical infrastructure means that there will be an explosion in new value to be competed for.

The value derived from today's personal car is fairly equally split between upstream (raw materials to finished vehicle) and downstream (all other parts of the value chain), with the customer self-aggregating services such as fuelling, insurance and service, maintenance and repair. Focusing on the downstream, we estimate that the revenues associated with a personally owned vehicle over a ten year period today would be approximately £30,000. By 2030, in an EV-AV-MaaS world, we estimate the downstream value could well be ten times as big as this, driven largely by new and incremental revenue streams enabled by the digital ecosystem.

Historically the transportation industry has operated along largely linear value chains. This explosion in value available will encourage previously disconnected sectors to converge on mobility, as it develops into a complex ecosystem of interconnected and interdependent value chains. As part of this, we expect to see a multitude of new entrants taking a share within the market, whilst there will also be unprecedented levels of partnership and collaboration as various players seek to design these new solutions.

We expect these forces to result in fundamental power shifts within value chains and the ecosystem. Incumbents and perhaps even entire sectors that have enjoyed years of strong, steady revenues and a good share of the value chain may be completely eliminated whilst opportunities for new services and thus new entrants will emerge. This will happen across sectors, meaning organisations will need to evaluate and redesign their financial, business and operating models including:

- In automotive, where we expect to see a bifurcation in the market. Some incumbent OEMs will remain "˜Metalsmiths', manufacturing ever more sophisticated vehicles but losing the customer interface as they sell into mobility services fleets. Meanwhile, others will evolve to become new "˜Grid Masters' which both manufacture the vehicles but also provide platforms for a variety of customer (mobility) services. Vehicle brands and driving performance may cease to be the key purchase decision criteria as customers look instead for a strong user interface and vehicle utility in an AV-MaaS world. This could well open the door for more consumer oriented technology players to become the customer interface.

- From an energy perspective, the decline in ICE vehicle sales and the impact on the vehicle parc will significantly reduce demand for hydrocarbon fuel sales for oil and gas firms. These firms will have to take measures to ensure they are not left with stranded assets. Meanwhile, adoption of EVs will increase the demand for power and utility services and infrastructure, and new vehicle charging business models will emerge.

- For governments, one immediate value chain implication stands out. A decline in hydrocarbon fuel sales, subject to fixed rates of duty per litre as well as the standard rate of VAT, will result in a significant reduction in the government tax take on vehicle fuelling, which recent press estimates put at £28bn a year. Governments globally will need to assess the impact on their spending and potential alternative ways of raising tax revenue through, for example, taxing miles travelled. Then there's the detrimental social impact of likely job losses in sectors such as commercial driving. Governments may need to commit more to social support, however, growth of EV-AV and MaaS will generate new sectors, new employment roles and skillset demands in other sectors across the ecosystem, offsetting some of this.

- Huge changes are also expected in the financial services sector. In insurance, AVs will mean that individuals no longer require insurance and providers will need to develop product liability oriented solutions to sell into major mobility services fleets rather than to individual customers. Within the payments market, new mobility services such as charge point payments and mobility services contracts will require new innovative payment mechanisms.

- In consumer markets, the significant amount of time freed up by people not having to drive will lead to retail, entertainment and health revenue opportunities as individuals consume vast volumes of content as they travel.

- The traditionally slower-paced infrastructure market will be impacted principally through the introduction of supporting data networks for V2V and V2G sensing and communication. Local transport authorities will need to evolve to manage not only the physical infrastructure but also the data exchanges, integration and maintenance. Other infrastructure players such as car parks will also be disrupted as AVs will drop off passengers and move on to collect others (or re-charge) rather than park. As a result, current parking service companies will need to reconsider how they extract value from the ecosystem.

- Data "“ the key foundation of future mobility "“ will see huge opportunities for telco, tech and media organisations across the emerging interconnected ecosystem, as AVs generate and use unprecedented levels of data, and mobility services providers depend on the digital platforms and databases to execute their services.

The above is not an exhaustive list but what is abundantly clear is that disruption will reverberate across a multitude of sectors and that roles in the future value chains and mobility ecosystem have yet to be decided. As incumbents, new entrants and start-ups compete for a share of the prize, each will have to consider where to play and how to win. Companies will have a small window of opportunity to get on the front foot, positioning themselves to shape the future ecosystem. Being a first mover, by securing beneficial partnerships, acquisition targets and structuring their internal financial, business and operating models to benefit from the new world, will be key. Those who don't act risk being left behind.

At KPMG, we believe we are at the beginning of a truly transformational journey, with an accelerating pace of change. The strength of consumer demand, as well as the rate of change of technological development for vehicle electrification and automation is increasing exponentially. The disruption will be significant and it will come with both great opportunities and risks. We are excited to play a key advisory role in the journey ahead.

Mobility is critical for population hubs and economies to function and grow. From a consumer perspective, passengers want to get from A to B in an economical, convenient and safe manner. Concerns such as environmental and health impacts are also becoming increasingly important and subject to public policy scrutiny. In contrast, mobility systems today suffer from congestion, inefficiency, human-driven accidents and high prices, which leads to detrimental social and economic consequences.

We are now witnessing a real shift in consumer demands and the way they view mobility. For example, from an economic point of view consumers are transitioning from asset ownership to access, especially in urban areas. KPMG's Global Automotive Executive Survey (2017) found that more than one in three consumers agreed that 50% of today's car owners will no longer want to own their own car by 2025. Similarly, recent Department for Transport statistics show that the percentage of men in England aged 17-20 holding a full UK driver's license has fallen from 51% in the mid-1990s to just 33% in 2016 (and from 81% to 68% for men aged 21-29). This can be partly attributed to the demand for convenience and the resultant emergence of on-demand private car hire firms such as Uber and Lyft, where at the click of a button a car will turn up in minutes. Then from a safety perspective, the emergence of AVs should enable new waves of untapped mobility demand from young people and seniors, offering safe independence where options were previously few.

Commercial goods carriers place similar demands on mobility systems "“ to be economical, safe, efficient and "˜green'. We are already starting to see this play out in HGV platooning trials, most notably in Europe and the US, where this technology is expected to cut operating costs substantially and reduce CO2 emissions by up to 10% (according to the European Automobile Manufacturers Association). Meanwhile, digitally enabled connectivity has led to the emergence of digital freight brokerage companies that seek to address the inefficiency issue evident in the significant proportion of trucks that run empty in Europe and other continents.

The impact of all this will be dramatic. KPMG estimates that in the UK for example, total passenger miles travelled could increase by up to 10% between 2015 and 2030. This will largely arise from additional trips taken by the young and elderly in AVs, as well as greater access to on-demand mobility services providers. These vehicles will increasingly be owned by fleets and will be heavily utilised assets much in the same way taxis currently are, in contrast to the average passenger car which today stands idle 95% of the time. As a result, this could mean a decline in overall car sales by 2030.

That said, our view is that future mobility solutions, and especially AV and MaaS, will have a significant, positive impact on global economies. This will mainly arise from consumer time freed up (not having to drive), more efficient journeys contributing to greater labour productivity and flexibility, as well as the value from greater telco and "˜smart' infrastructure demand and new digital and service sector revenue streams. Indeed, our 2015 analysis for the UK alone estimated the impact to be £51bn added to annual UK GDP by 2030 (or a c. 2.5% increase on current levels). Given the pace of change in the market, that figure is likely to be even higher now.

The growth in consumer spending power from time freed up and new possibilities whilst travelling, as well as the emergence of new vehicle technologies and the maturation of the supporting digital and physical infrastructure means that there will be an explosion in new value to be competed for.

The value derived from today's personal car is fairly equally split between upstream (raw materials to finished vehicle) and downstream (all other parts of the value chain), with the customer self-aggregating services such as fuelling, insurance and service, maintenance and repair. Focusing on the downstream, we estimate that the revenues associated with a personally owned vehicle over a ten year period today would be approximately £30,000. By 2030, in an EV-AV-MaaS world, we estimate the downstream value could well be ten times as big as this, driven largely by new and incremental revenue streams enabled by the digital ecosystem.

Historically the transportation industry has operated along largely linear value chains. This explosion in value available will encourage previously disconnected sectors to converge on mobility, as it develops into a complex ecosystem of interconnected and interdependent value chains. As part of this, we expect to see a multitude of new entrants taking a share within the market, whilst there will also be unprecedented levels of partnership and collaboration as various players seek to design these new solutions.

We expect these forces to result in fundamental power shifts within value chains and the ecosystem. Incumbents and perhaps even entire sectors that have enjoyed years of strong, steady revenues and a good share of the value chain may be completely eliminated whilst opportunities for new services and thus new entrants will emerge. This will happen across sectors, meaning organisations will need to evaluate and redesign their financial, business and operating models including:

- In automotive, where we expect to see a bifurcation in the market. Some incumbent OEMs will remain "˜Metalsmiths', manufacturing ever more sophisticated vehicles but losing the customer interface as they sell into mobility services fleets. Meanwhile, others will evolve to become new "˜Grid Masters' which both manufacture the vehicles but also provide platforms for a variety of customer (mobility) services. Vehicle brands and driving performance may cease to be the key purchase decision criteria as customers look instead for a strong user interface and vehicle utility in an AV-MaaS world. This could well open the door for more consumer oriented technology players to become the customer interface.

- From an energy perspective, the decline in ICE vehicle sales and the impact on the vehicle parc will significantly reduce demand for hydrocarbon fuel sales for oil and gas firms. These firms will have to take measures to ensure they are not left with stranded assets. Meanwhile, adoption of EVs will increase the demand for power and utility services and infrastructure, and new vehicle charging business models will emerge.

- For governments, one immediate value chain implication stands out. A decline in hydrocarbon fuel sales, subject to fixed rates of duty per litre as well as the standard rate of VAT, will result in a significant reduction in the government tax take on vehicle fuelling, which recent press estimates put at £28bn a year. Governments globally will need to assess the impact on their spending and potential alternative ways of raising tax revenue through, for example, taxing miles travelled. Then there's the detrimental social impact of likely job losses in sectors such as commercial driving. Governments may need to commit more to social support, however, growth of EV-AV and MaaS will generate new sectors, new employment roles and skillset demands in other sectors across the ecosystem, offsetting some of this.

- Huge changes are also expected in the financial services sector. In insurance, AVs will mean that individuals no longer require insurance and providers will need to develop product liability oriented solutions to sell into major mobility services fleets rather than to individual customers. Within the payments market, new mobility services such as charge point payments and mobility services contracts will require new innovative payment mechanisms.

- In consumer markets, the significant amount of time freed up by people not having to drive will lead to retail, entertainment and health revenue opportunities as individuals consume vast volumes of content as they travel.

- The traditionally slower-paced infrastructure market will be impacted principally through the introduction of supporting data networks for V2V and V2G sensing and communication. Local transport authorities will need to evolve to manage not only the physical infrastructure but also the data exchanges, integration and maintenance. Other infrastructure players such as car parks will also be disrupted as AVs will drop off passengers and move on to collect others (or re-charge) rather than park. As a result, current parking service companies will need to reconsider how they extract value from the ecosystem.

- Data "“ the key foundation of future mobility "“ will see huge opportunities for telco, tech and media organisations across the emerging interconnected ecosystem, as AVs generate and use unprecedented levels of data, and mobility services providers depend on the digital platforms and databases to execute their services.

The above is not an exhaustive list but what is abundantly clear is that disruption will reverberate across a multitude of sectors and that roles in the future value chains and mobility ecosystem have yet to be decided. As incumbents, new entrants and start-ups compete for a share of the prize, each will have to consider where to play and how to win. Companies will have a small window of opportunity to get on the front foot, positioning themselves to shape the future ecosystem. Being a first mover, by securing beneficial partnerships, acquisition targets and structuring their internal financial, business and operating models to benefit from the new world, will be key. Those who don't act risk being left behind.

At KPMG, we believe we are at the beginning of a truly transformational journey, with an accelerating pace of change. The strength of consumer demand, as well as the rate of change of technological development for vehicle electrification and automation is increasing exponentially. The disruption will be significant and it will come with both great opportunities and risks. We are excited to play a key advisory role in the journey ahead.

KPMG: Value chains will be disrupted in the future mobility ecosystem

Modified on Friday 26th January 2018

Find all articles related to:

KPMG: Value chains will be disrupted in the future mobility ecosystem

Add to my Reading List

Add to my Reading List Remove from my Reading List

Remove from my Reading List